16. Sam Renda ~ in her prayer

Sam Renda’s poetry compels us to focus on the moments that shape our story, urging us to interrogate our own gaze and reckon with what we see or intentionally overlook. She is deliberate in her use of haiku, pouring her own vulnerability and empathy into each poem, inviting the reader to do the same. For as she notes in her essay, “haiku is the form that asks the reader to do the most work.”

Her works deftly engage with critical themes such as the struggle for acceptance, social injustice, and the fluid nature of identity. She gives voice to those who are often marginalized, such as the unhoused and workers in low-prestige jobs, capturing the vibrant and sometimes rough realities of our cityscapes with poems like “two-day rain” and the “street sweeper’s broom twirl.” She explores the subtle ways societal pressures manifest, yet finds a new, inclusive perspective on belonging and “otherness.”

The poems are rich with striking imagery, from the harshness of a “ripped root” or an “icy garúa” (mist) on naked skin, to the “soft curl of incense” and her seed-borne “prayer.” She does not flinch from what is hard nor the labor of softness. Renda tells her story to tell ours, and invites our voice to the chorus.

Matt Snyder, confluence associate editor

poems

tumbleweed

her first step at rebuilding

a childhood record

a little more

cowboy in my walk

new blue boots

new haircut

my prefix switches

back to sir

a homeless man

hunched on the subway steps

two-day rain

the landscape

of my naked skin

icy garúa

as if everything

about me breaks her —

ripped root

tending

the mother-hollow

driving rain

driving rain

an old woman

spits back

soft curl

of incense

mourning prayer

woodwork class

I sand with the grain

thinking of nothing

shadow puppets

consulting her skin's

memory

murmur

through a reedbed sea

drunk swallows

war memorial

rough-cut bricks

shed their foundation

mother's diamonds

the ongoing price

of this silence

thistle pods

in her prayer for the dying

the world

street-side cafe

today again I don't see

that beggar

luminescent sea

all the little things

we think we'll remember

hibiscus season

the street sweeper's

broom twirl

comic book store

I buy back a piece

of ten years old

all the places

I have yet to go

streetlamp moth

marriage office

she asks which of us

wants to be the husband

development protest

an endless line of ants

marches alongside

a little softness

in the homeless man's smile

whispering weeds

community

in another place

this bare eucalypt

Frogpond

Modern Haiku

Acorn

Autumn Moon Haiku Journal

Kingfisher

The Mamba

essay

filling in the blanks

For me, haiku has always been a multi-faceted lens. I came to these short, observant poems from a love of nature and quickly found their counterpart, senryu, to be an almost perfect vehicle for expressing my fascination with human nature as well. A well-crafted haiku or senryu can capture a poignant moment as well as any longer poem. Perhaps more so, because these forms force the writer to distill that moment down to its essence. To the very center of the feeling or mood or observation that caught their attention in the first place.

More recently, I’ve found haiku giving voice to my own inner world, illustrating the complex space I inhabit as a queer, intersex, “neuro-something” poet. Some of those poems speak to my childhood sense of unbelonging. Of being “matter out of place.” Some to relationships with family or self. Or to a newly growing sense of deeper engagement with the world.

Often, I write the same themes as applied to others. Especially those “othered” by society. The street cleaner. The old man sleeping on the corner by the school, studiously ignored by passers-by.

Haiku to me, like all poetry, is a mirror held up to human life. Of all poetry, however, I think haiku is the form that asks the reader to do the most work in filling in the blanks. The form that most begs to be read and reread, until the reader’s own understanding deepens.

I find that the best haiku are those so subtle that I come back to them again and again, pulled by some imperceptible nuance of meaning that I know is there but have yet to uncover. The poems that awe with their multiple layers. And with the gentle, profound, bewitching, or gut-punch “aha!” moment that always accompanies a new understanding of them.

commentaries from Fellows

Deborah Karl Brandt, Anthony Q. Rabang & Cynthia Bale

Deborah Karl-Brandt

These poems touch my heart. I wish everyone would read them. Sometimes they are gentle,

comic book store

I buy back a piece

of ten years old

at times they will hit you right into your face

marriage office

she asks which of us

wants to be the husband

but they are always respectful and offer a new perspective on how to view the world.

new haircut

my prefix switches

back to sir

Dealing with the themes of otherness, family relationships, social injustice, and the struggle to find one's place in this world are the core themes in Sam Renda's work. Each poem gives us the opportunity to experience different perspectives of marginalized groups. As long as people live in societies, there will be individuals who have to fight for acceptance and belonging. They are disregarded, shamed, physically harmed, or have to cope with other forms of oppression. And the question arises: Why does it have to be this way? Why can't we just become more inclusive, open-minded, gentle, and accepting? It would be a much kinder world in which to live.

a little more

cowboy in my walk

new blue boots

This last poem tells of the lifelong journey of a person who no longer has to conform, but has created their own place in the world. And just as the lyrical persona finds this place, so do I. I finally feel that there is a place for me too, where I am meant to be and where I belong.

Anthony Q. Rabang

Sam Renda has meticulously chosen her words and mixed-matched them effectively in her contemporary haiku and senryu, creating a voice that captures both imagination and poignancy. She gives voice not only to herself and those who identify with her, but to everyone in the community: the streetsweeper, the homeless and the beggar behind the picket lines.

In the expanding ocean of queer short poems, Renda’s haiku and senryu are engaging and relevant. Her poem “marriage office” reveals the pervasiveness of machismo culture; even in same-sex marriages, society pressures queer couples to assume outdated normative gender roles, “the husband as breadwinner” and “the wife as homemaker.” She also touches on power dynamics, that in order to be seen as “strong,” “capable,” and a “leader,” one must struggle to conform to traditionally masculine traits such as having a buzz cut or the archetypal cowboy look. Masculinity stereotypes persist in the media and in Hollywood, and it can be toxic in perpetuating prejudice in the workplace or within marriage. Such portrayals create a glass ceiling for individuals who do not express traditionally masculine traits, making leadership roles less accessible to them, or even placing them on a pedestal with unfair expectations.

Furthermore, the subtle depiction of the poor and their daily struggles in Renda’s “a homeless man”, “a little softness” and “street side cafe” feel close to home. However, our tendency to romanticize the resilience of the poor and remain silent in the face of social injustice only breeds contempt if it lacks a call to demand our fundamental rights and hold those in power accountable. Renda successfully avoids this pitfall with her poem “development protest” and invites the reader to march in solidarity with the poor.

development protest

an endless line of ants

marches alongside

Cynthia Bale

Sam Renda’s poems ask readers to interrogate their own gaze – what do you see, and what do you look away from? The vibrant cityscapes in her work embrace people that society often prefers to ignore: unhoused people, beggars, and workers in low-prestige jobs. In “hibiscus season”, she shows us the beauty and playfulness to be found in something as ordinary as the twirl of a street sweeper’s broom, and in “driving rain,” we meet a woman who cares so little for social conventions that she spits back at the inclement weather. Renda does not limit this consideration to humans, either; in “development protest” and “streetlamp moth”, she includes her insect neighbors’ lives in her reckoning. Even weeds receive this treatment when “a little softness” highlights the gentleness their whispers offer.

Sometimes, however, our choice to look away is deliberate, as in “mother’s diamonds”, which deftly directs the reader’s focus away from the opening sparkles to a relationship so fractured that only bribery keeps a tenuous peace. These elisions of attention are not always so sinister, however; “luminescent sea” pokes gentle fun at the fallibility of human memory, and “woodwork class” shows us how freeing it can be simply to let go of conscious thought and work with our hands, following patterns nature has already laid out for us.

The world is always looking back, too, and I really enjoyed the lighthearted way Renda’s poems engage with gender presentation – changeable as boots or arbitrary as whose name goes in the non-applicable blank on a form. We don’t have total control over how we’re perceived, but as in “new haircut”, we can make changes and look wryly upon the results, asking the world to evaluate its gaze just like these poems invite us to do for our own.

Thank you for reading!

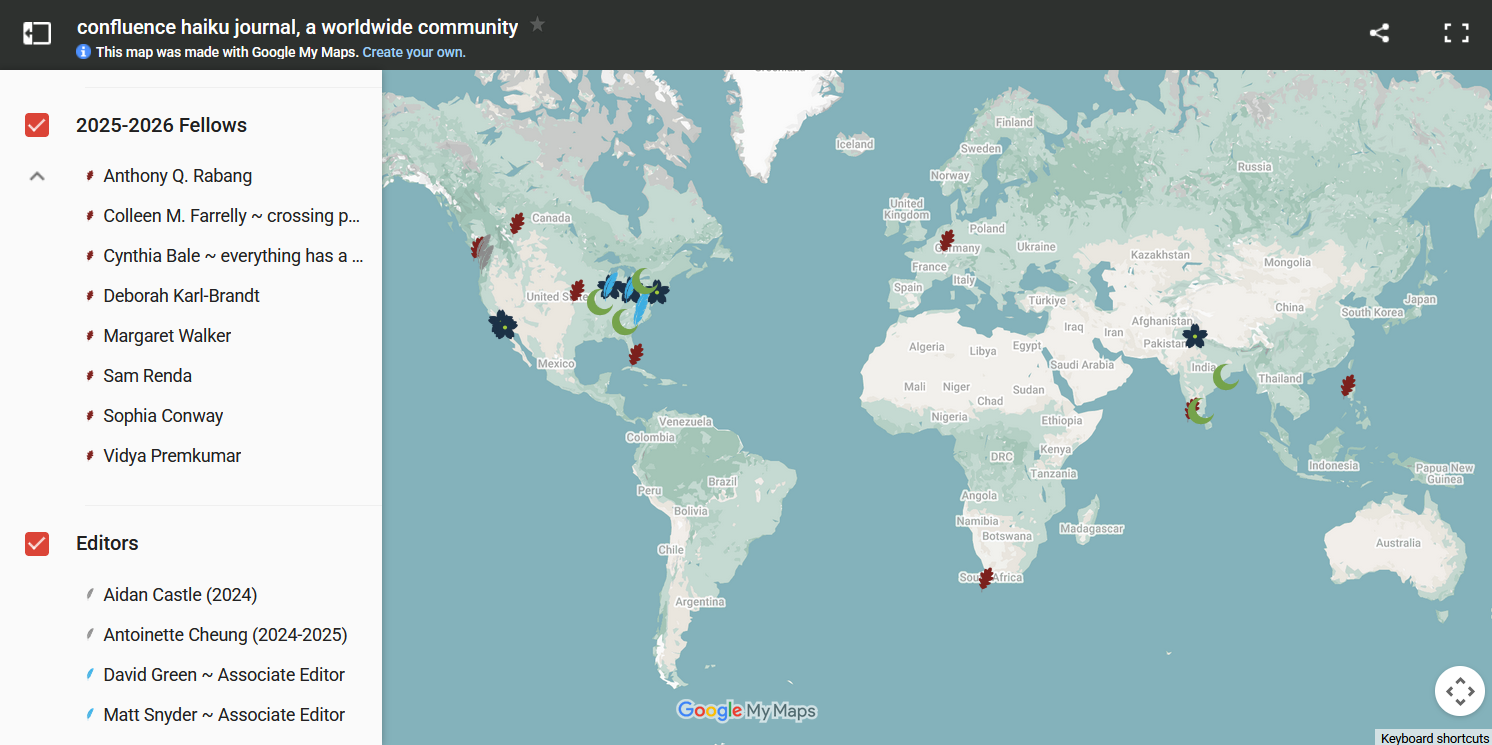

We also want to follow up on the map view of our worldwide community. In our last issue, we shared the map but later realized that the emailed version of the newsletter didn't include the embedded content. Below you can now see an image of the map, and you may click through to the live map to navigate and filter our world.

We invite you to continue the conversation by hitting the "comment" button below and letting us know where you're reading confluence from. We'd love to hear your favorite poem of Sam's (literally: feel free to post your own reading!) and share any responses to her work as well. Sam and the editors look forward to reading and responding to your comments.

If you liked the issue, we invite you to share this with others in your community. Stay tuned for the next issue in January, which will feature work by Fellow Deborah Karl-Brandt.

Member discussion